Venezuela – Jewish life in Caracas

How the Jewish community of Venezuela survives under President Nicolas Maduro

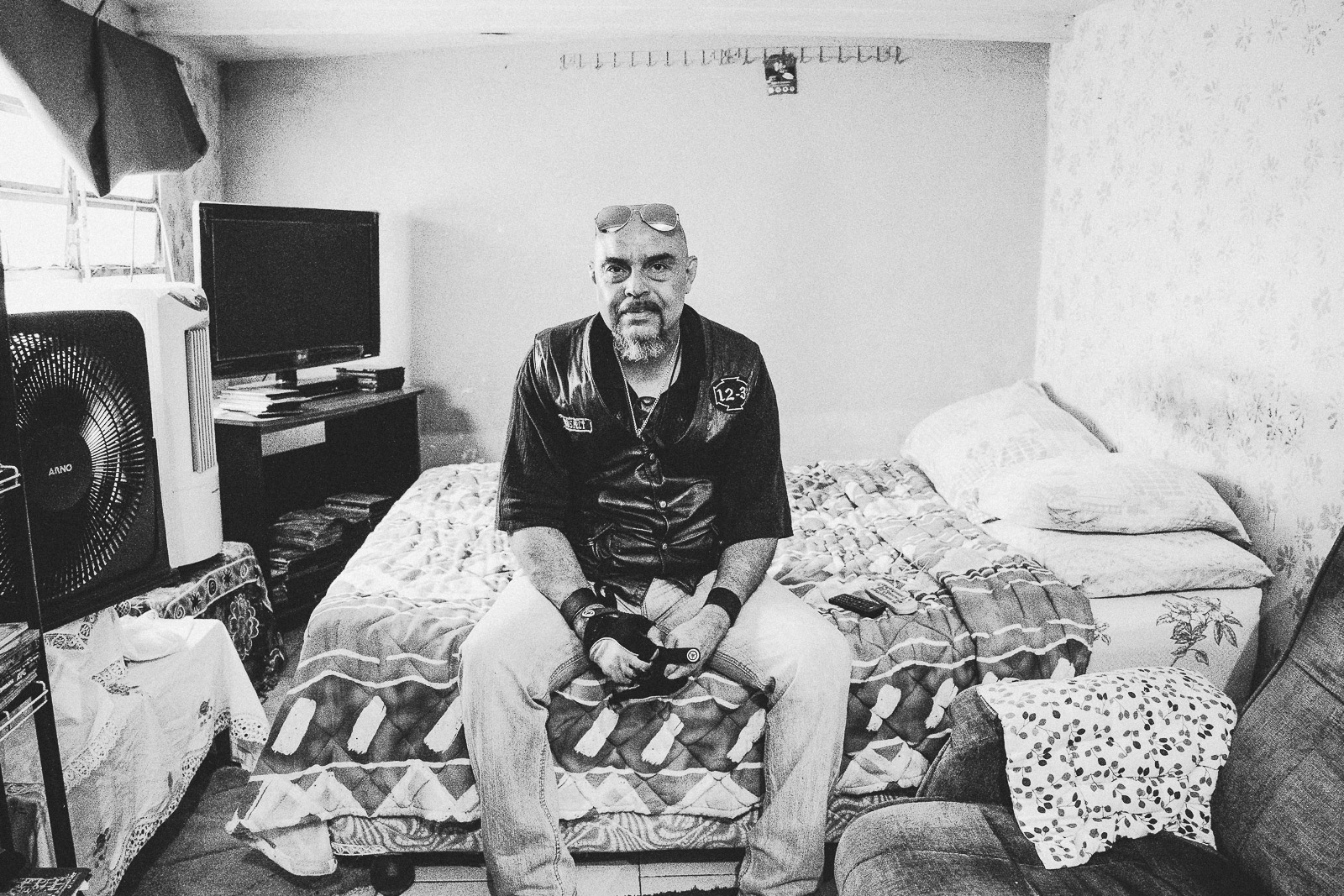

Many of their ancestors had fled the pogroms and the Holocaust. Their families adapted to the tropics and contributed to the progress of their new homeland. They were survivors. These days, a younger generation of Jewish people in Venezuela is again struggling to survive, in the midst of one of the gravest humanitarian catastrophes of contemporary history. Their community and their religion is the glue that holds their lives together in a collapsed country.

From the 1940s to the 1990s, Venezuela was home to a small but flourishing Jewish community. When president Chávez´s first mandate commenced in 1999, an estimated 25.000 Jews lived in the country, most of them in the capital Caracas. Today, only about 7000 remain. The others have joined the mass exodus of millions of Venezuelans.

The community has become more closed off

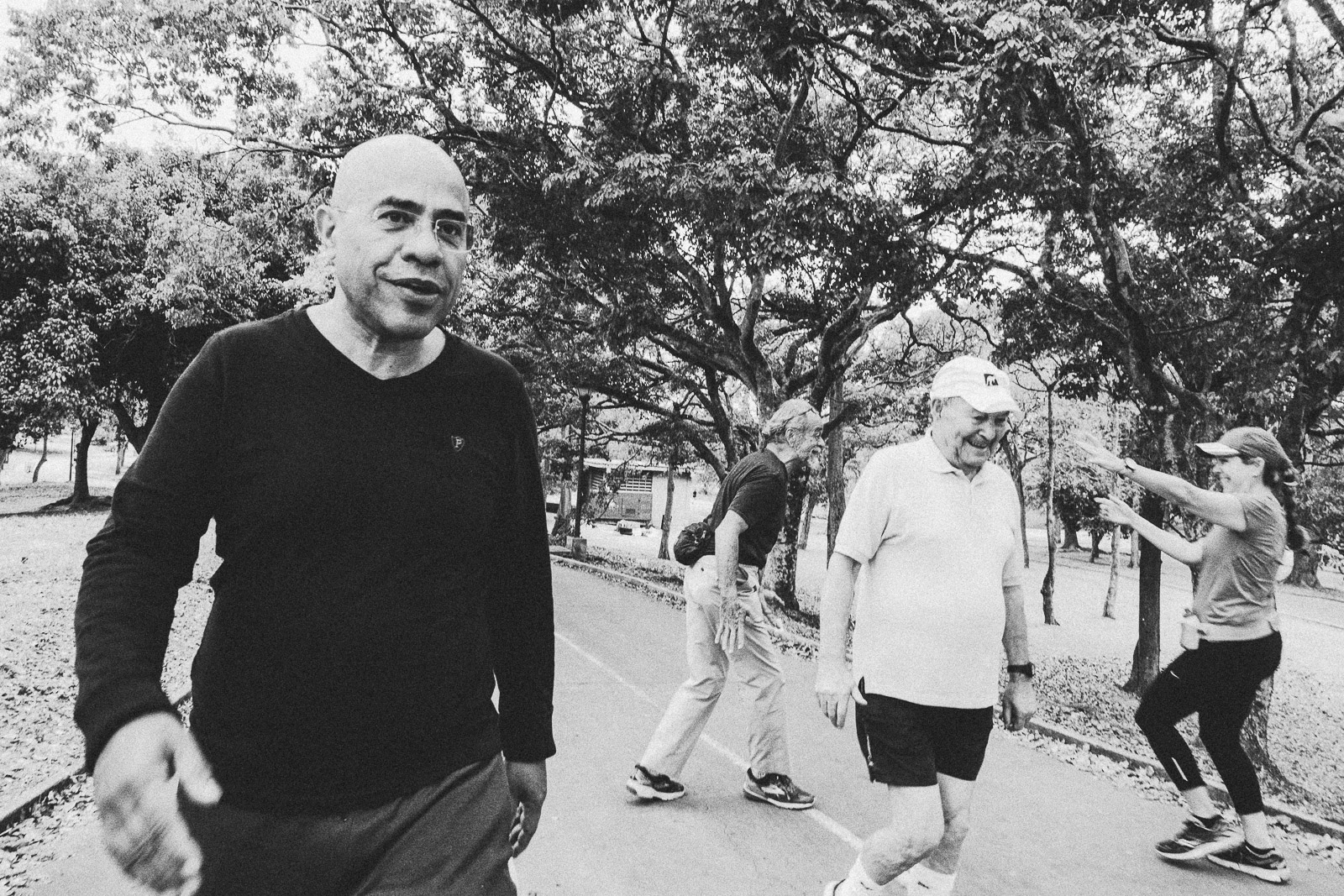

Ten years later, I was again in Caracas. The city had changed for the worse. Supermarkets were full with imported goods but only very few Venezuelans could afford them. Constant power outages had levelled the remains of the economy. Journalists were thrown into prison or beaten up by the state police. Opposition leader Juan Guaido was constantly calling his followers to march on the streets but most Venezuelans were tired of risking their lives in protests which in the end did not change anything. Albeit US-sanctions, the responsibles for this humanitarian, economic and political disaster, president Nicolas Maduro and his entourage, were not willing to convene free elections. All in all, it was a nightmare.

And there I was, somehow trying to reconnect with the Jewish community. I started calling old numbers. Almost all were out of service. I went to see friends. I interviewed one of the official spokespersons of the community. I even randomly visited kosher bakeries and butcheries in San Bernadino.

No-one wanted to appear in front of the camera. It was obvious, the political climate had changed. “The community is afraid of the government and tries to go unnoticed and to avoid anti-Semitic acts or to ensure that it can remain in the country and continue with its religious practices”, a Jewish friend had written me. The Jewish community had become more closed off. I started to doubt: why was I so interested in the topic anyways. Was it some unconscious German feeling of guilt?

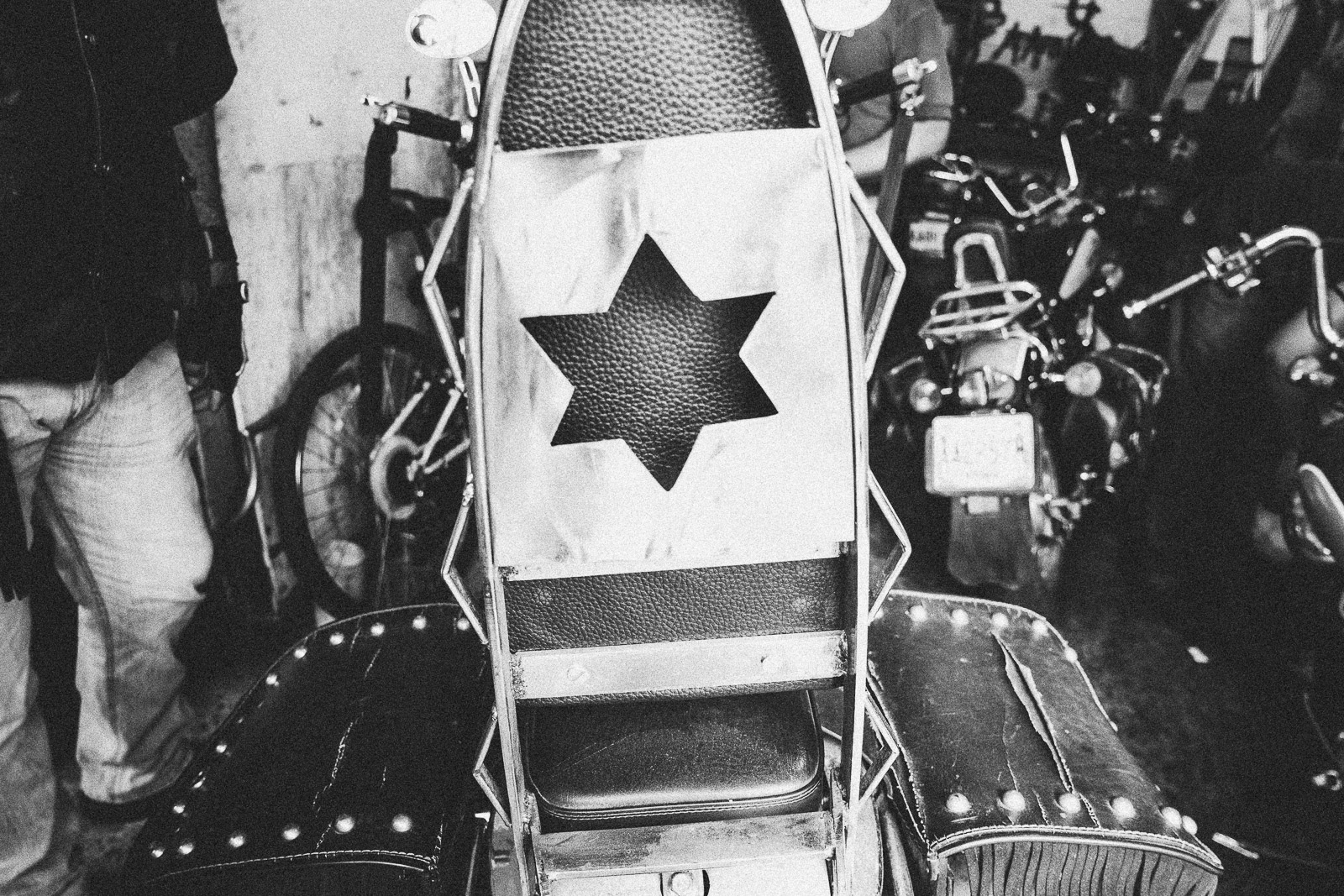

Religion is resilience

One particular afternoon I sat in the neat garden of a wealthy textile businessman in a high class neighbourhood of Caracas. Electricity had gone out again in the entire country. I could not work. I could not shower. I could not buy groceries. I could move in the city only with difficulties. I began to feel the way most Venezuelans felt. That I had lost focus. I was simply waiting for something I could not decipher.

My Jewish acquaintance asked me if I was religious. I told him that I did not belong to any religious community. “This must be hard”, he contested. “You must feel terribly alone.”

Religion was not only about praying and believing. For many people it was about being part of a community and supporting each other. It permitted resilience. Finally, it made click in my head.